Guiding Question, class 2 of Seneca's Phaedra

This is a heads up for the Guiding Question for the Seneca Phaedra part 2 class. But it's also a guiding question for the Roman Tragedy unit as a whole. The question has to do with the following sentence quoted from the (not assigned for class) Brill's New Pauly article on Roman tragedy:

"The content of Roman tragedy is not 'tragic.' ... "

Then, commenting specifically on Senecan tragedy,

"In their positive aspects Seneca’s heroes are Stoic wise men, in their negative aspects monomaniacal criminals."

(Brill's New Pauly)

On reading that, my own first reaction was, How's that even possible? It's tragedy, right? But then I thought, Hmmm, maybe Brill's is onto something. . . .

So, what do you think Brill's New Pauly means when it says that "the content of Roman tragedy is not 'tragic' "? What assumptions seem to lie behind Brill's generalization? Does it seem a fair assessment? And based on readings through Seneca Phaedra part 2 (that includes your impressions of Greek tragedy since the beginning of the semester), what do you think Brill's New Pauly means when it says that "the content of Roman tragedy is not 'tragic' "? What assumptions seem to lie behind Brill's generalization? Does it seem a fair assessment?*

* If you'd like to read the Brill's article in question, you're of course free to do so, though it's not required. In any case, I don't believe that the author, Thomas Baier, fully explains himself.

Text Access

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Phaedra. Trans. E. F. Watling. Four Tragedies and Octavia. 2 ed. Penguin Classics. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1966. 95-150. (Available via bookstore.)

Introduction to Rome

Rome and its empire are, it seems, much on people's minds these days. One TikToker's boyfriend confesses to thinking about them three times a day. Says he, "There's so much to think about."

And so there is. One thing to think about is the fact that Roman culture, despite its many connections to Greek culture, was its own thing and needs to be treated as such — read on!

Historical

First, these are Romans, not Greeks. Their language was Latin, though educated Romans also knew Greek. Clearly, though, Roman interest in things Greek gained steam as a result of Roman conquests, third through first century BCE, in culturally Greek lands: southern Italy, Greece proper, the great kingdoms of the Hellenistic East. To quote the Roman poet Horace, "Captive Greece captivated its barbaric captor and brought civilization to Latin peasants" ("Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artis | intulit agresti Latio," Epistles 2.1.156-157). At the same time, elements of Roman culture, things like Roman baths, gladiatorial entertainments, and Roman dining customs, spread to various provinces of the Empire.

Initially, the city, maybe better, village of Rome controlled only itself and surrounding territory. Eventually, though, Rome's empire grew to encompass virtually the entire world known to Mediterranean peoples. From Portugal to the Persian Gulf, from Britain to Egypt, Roman rule left its imprint on peoples and places that fell under its sway. All roads led to Rome, and by 212 CE, all free women and men residing within the Empire were made Roman citizens.

The idea of Rome as the Eternal City (urbs aeterna) has, over time, exerted considerable appeal, but we must not lose sight of historic developments that have a bearing on the evolution of Roman tragedy.

MONARCHIAL PERIOD: From the founding of the city (traditionally, 753 BCE) until about 512, Rome was ruled by kings

REPUBLICAN PERIOD: From about 512 until 44 BCE (the death of Julius Caesar), Rome was a republic (i.e., non-monarchy) of a basically oligarchic cast (i.e., characterized by rule by the elite few), though with democratic aspects (the people voted for officials and laws, but usually the vote was manipulated by the elite). Elected officials ("magistrates") and the Senate (senatus, "council of elders," largely made up of wealthy ex officials) administered the state; the People (populus) elected those officials and passed laws. It was during this period that Roman exposure to things Greek propelled the development of Roman literary culture.

PRINCIPATE: After a period of civil war and unsettled politics, a kind monarchy was imposed, with an emperor (princeps, imperator, Caesar, Augustus) ruling in collaboration (theoretically) with the Senate. That lasted from 27 BCE until the later third century CE. The early Principate saw the flowering of the kind of tragedy that Seneca wrote.

(With the accession of the emperor Diocletian, reigned 284-305 CE, comes full-on monarchical rule, the "dominate." Constantine's reign — 306-337 CE — saw the Empire's capital move east to Constantinople, present-day Istanbul. Constantine was the first Christian emperor, but all that lies beyond the purview of this course.)

Roman Theater

Though Italy had various native (i.e., non-Greek) theatrical-dramatic-poetic traditions, for instance, Atellan farce, phlyax farce, and Fescennine verse, Roman theater and drama largely took the path they did on account of Greek influence. During the period of the Roman Republic and early Empire, the state, often under the direction of officials called aediles ("EE-dials"), would organize entertainments that included the staging of comedies, tragedies, and other types of drama. Particularly popular were mimes (plays featuring slapstick and burlesque, and performed by women and men without masks) and pantomimes (a solo, silent, masked performer, male or female, dances a mythological story with musical accompaniment). Performances would be scheduled for major religious/public festivals called ludi, literally, "games." (Rome did not have dramatic festivals like the Greater Dionysia in Athens.)

In similar fashion, ambitious politicians and wealthy individuals, whether to mark the passing of an important personage or to celebrate a military triumph, or just to win votes, would often sponsor popular entertainments called munera ("gifts"; singular munus). Gladiators and dramatic performance were a mainstay of these ludi and munera. Roman drama was NOT staged competitively, nor did Roman playwrights produce plays in groupings like our Athenian tetralogies. These earlier Roman playwrights were often themselves of non-Roman origin and were attached to important Romans as patrons. This is very different from the situation in 400s and 300s Athens.

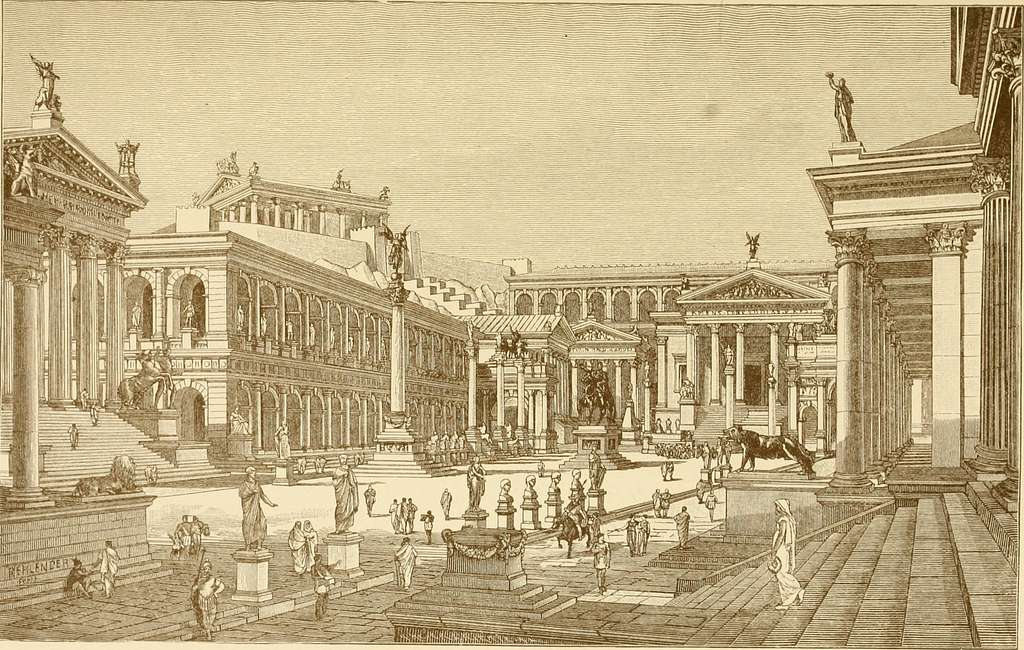

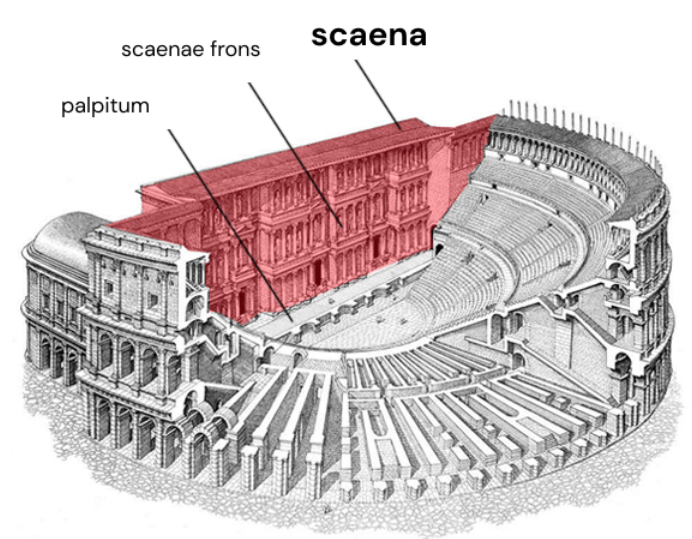

In the earlier period (ca. 240-55 BCE), Roman acting troupes would typically set up wooden stages in public spaces like the Roman Forum, often with other forms of entertainment (notably, gladiators) competing for the attention of the audience. In 55 BCE, the politician and general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus ("Pompey the Great") built the first permanent theater in Rome, the Theater of Pompey. Under the Empire and in cities from Spain to Syria, and France to North Africa, large and magnificently appointed outdoor theaters (we call them "theaters," not "amphitheaters") were built. These last could accommodate thousands of spectators and often boasted architecturally lavish stage backdrops. They would be multi-purpose spaces, suitable for dramatic/musical/rhetorical performances, gladiator shows, political meetings, you name it!

The performers of staged Roman comedy and tragedy would, like their Greek counterparts, regularly perform masked. They were normally all men, though see the exceptions, above, offered by mime and pantomime. Performed tragedy and comedy involved mostly the speaking of dialogue in poetic meter, but performers would also sing, as would choruses. One of the functions of choruses in Roman drama eventually became that of marking the divisions between acts.

Drama clearly had become popular among Romans, but their attitudes to theater and to acting were different from those of the Greeks. At Athens, successful performers, including actors, enjoyed considerable prestige. So, for instance, the playwright, director, and (early on in his career) actor Sophocles was elected to the office of stratēgos, "general," a signal honor for him (though we're told that he wasn't much good as a general). In the 300s BCE, the tragic actor Aeschines was an influential politician. Rome, however, could consider the acting profession to be disreputable, beneath the dignity of a citizen, especially, of elite citizens. Thus a late Roman source pronounces "those who have gone on stage for the purpose of performing in a play or to recite" to be infames, "infamous," that is, bereft of civil rights (Digesta 3.2.1, Julian). The same applied to sex workers, pimps, and gladiators. And yet, actors and gladiators could achieve considerable fame and fortune, so much so that senators and even emperors sometimes took to the stage or even to the gladiatorial arena. So, for instance, the emperor Nero (ruled 37-68 CE) regularly gave public voice recitals and, in so doing, scandalized polite Roman society.

The same did not, however, apply to the composition of drama. Thus it was okay for Imperial-era senators like Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE) and Curiatius Maternus (late first century CE) to write tragedies, which they did. It is not known if the tragedies of Seneca and contemporaries of his class were ever staged, or if they were, how they were staged, and before what sort of public. But, as C.J. Herington has brilliantly shown ("Senecan Tragedy," Arion 1966), early Imperial tragedy as exemplified by Seneca's plays is eminently performable and was quite plausibly experienced in live delivery stressing both dramatic and rhetorical aspects.

Roman Tragedy

Subgenres

We'll talk more in class about qualitative differences between Roman and Greek tragedy; here I provide a very sketchy intro to Roman examples of same.

Roman tragedy came in two, basic varieties:

FABULA CREPIDATA, or "play wearing the Greek boot," i.e., employing plots from Greek myth and probably adapting a Greek original.

FABULA PRAETEXTA, or "play wearing the fringed toga of a Roman high official," i.e., taking its plot from Roman history, whether remote or recent.

Style and Rhetoric

Unlike its fifth-century BCE Greek counterpart, Roman tragedy was heavily influenced by the rhetorical tradition, that is, by the education in public speaking that elite men and some women received during the period of Roman domination of the Mediterranean. In the Republican period, those influences, along with others stemming from archaic Italic religious and legal formulas, produced language that was often striking in its sound, its rhythm, and its structure of thought. Consider the relentless thrumming of the "m" sound (alliteration) in the following line from Accius' Atreus:

Maior mihi moles, maius miscendumst malum.

"More moil for me! A bigger bane to brew."

(Say it with a deep, boomy voice: Remains of Old Latin II, pp. 382-383.)

Archaeological Museum

One of the chief features of Roman tragic rhetoric, as of Greco-Roman rhetoric generally, was the sententia (in Greek, gnōmē), an often highly compact verbal package meant to deliver a knock-down punch — I sometimes refer to them as "notable quotables," as some of them became familiar sayings.

The most famous of those sententiae concerns a figure much loved by Roman tragedy, the tyrant king. Thus from the same play as the previous quotation comes the following, spoken by that play's tyrant protagonist, Atreus:

Oderint dum metuant.

"Let them hate so long as they fear."

(Say it with an arrogant sneer, maybe while twisting your mustache: Remains of Old Latin II, pp. 382-383.)

In just three words the Latin sums up the entire philosophy of the tyrant.

Seneca, a master of rhetoric generally, was a peerless practitioner of the sententia in his tragic poetry.

Introduction to Senecan Tragedy, to Seneca's Phaedra

Times: The Early Principate

Politics

In 27 BCE, the soon-to-become Augustus, the last man standing after decades of violent and disruptive infighting between Rome's leaders, ceremoniously returned sovereign power to the Senate and People of Rome (the SPQR, or SENATVS·POPVLVS·QVE·ROMANVS), only to have it returned right back to him through a series a measures endowing him with close to monarchic — though not total — control of the state, or RES·PVBLICA. The emperor styled himself "first among equals" (princeps inter pares). The emperor's subjects, poets like Ovid, styled him son of a god, and destined to become a god. (Octavian-Augustus was the adoptive son of Julius Caesar, who, after his assassination in 44 BCE, was declared a god by the senate.) The name "Augustus" itself means "venerable," "majestic"; the emperor's guardian spirit, his genius, became the object of public worship.

Returning to the autocracy engineered by Augustus, it verifiably provided a welcome degree of political stability. But it also meant that the Senate, long the most powerful and aristocratic governing body at Rome, had its powers greatly reduced; the old Republic was, to all intents and purposes, dead. Things were better, but with so much power concentrated in one person, the ancestral Roman hatred of kings came face to face with the reality of one-man-rule, dynastic strife, and diminished power for the old ruling class.

Things deteriorated under the rule of the next four Caesars: the misanthropic Tiberius (r. 14 CE-37), the sociopath Gaius (aka Caligula, r. 37-41), the scholarly and capable, but too-easily manipulated, Claudius (r. 41-54), the and the more or less unhinged (a matter of debate) Nero (r. 54-68). This was a period when persons of rank had to watch their backs at all times. Any word or deed capable of interpretation as disloyalty to the emperor or his family could bring with it charges of treason. Members of the old senatorial class, because they could not openly criticize Caesar, i.e., the emperor, had taken to doing so covertly, for instance, through the writing of supposedly mythological or historical works. Hence tragedies with titles like Cato (Cato the Younger, Republican martyr) or Atreus (the extremely evil Greek king) as a way of maintaining "plausible deniability" when voicing protest. Yet even the faintest hint of disloyalty in a line of drama could prove lethal for the playwright.

Philosophy

At the same time, two philosophies from Greece were competing for the minds of Roman intellectuals. From a Roman perspective, neither philosophy appealed primarily for its contribution to ancient science, metaphysics, or logic. (Stoic logic was actually a stupendous achievement unequaled until little more than a hundred years ago!)

Dor Stoics, what really mattered was ethics: that branch of philosophy concerned with the art of living, which is to say, with the path to happiness. Hence the Roman philosopher's — Seneca's — concern with questions addressing the possibility of a moral order in a seemingly chaotic world, of independent agency in the face of fate, the problem of suffering and evil, and so on — concerns arguably shared between Seneca's prose and tragedy.

As to the philosophies in question, they can be very briefly summarized as follows:

- Epicureanism, which taught that the gods exist but ignore human beings, who should imitate the gods by seeking to live lives totally free from disturbance: ambition, lust, but mostly the fear of death (the Epicureans believed in no afterlife)

- Stoicism, which taught that human beings should seek to "live in accordance with nature" (kata phusin, secundum naturam). Nature, the Stoics believed, is guided by rational principles: logos (Greek) or ratio (Latin). By living thus, one achieves both wisdom and virtue, and therefore, happiness. ("The mind, in its effort to gain wisdom, takes its start from those things that follow nature, and thus achieves knowledge of the good," Cicero De finibis 3.33.) Besides wisdom, nothing matters. Wealth, health, power, pleasure — all of it, though generally viewed as advantages, were viewed by the Stoics not as evil but as "indifferent" (adiaphora, indifferentia)

- Connected with early Imperial Roman Stoicism was a fashion for philosophical suicide: deaths staged as acts of protest against the corrupt rule of the Caesars. Especially for the Stoics, suicide could represent honorable release from intolerable situations. One of those to die in this way was our playwright, Seneca

Note that Seneca was a committed Stoic though also clearly knowledgeable in Epicureanism; you'll find evidence of both philosophies in his works.

Rhetoric

Finally, a word about rhetoric. Higher male elite education in Seneca's day centered around two subjects: philosophy and rhetoric, with the emphasis ultimately on rhetoric. For even under the emperors, achievement in rhetoric, the art of persuasion, was the aristocrat's ticket to success in politics. (Yes, politics of a sort continued to be practiced.)

Young men were, accordingly, heavily schooled in rhetoric. At the same time, rhetoric itself came to be cultivated as an art form in its own right, with master rhetoricians composing and publishing demonstration pieces — "declamations" (declamationes) — on a variety of often fictitious or mythological topics. Rhetoric of this type penetrated all corners of Roman literature, both poetry and prose. Seneca's father compiled a collection of declamations for use by his sons (still survives); Seneca's tragedies and other works often betray evidence of this rhetorical training.

See the Introduction to Roman Tragedy page for sententia as a feature of Roman rhetoric and tragedy; also below.

Performance

We know next to nothing about whether Senecan tragedy was performed in public and, if it was, how it was performed. One recent discovery at the Roman city of Pompeii, in southern Italy, basically confirms that in the middle to later first century CE, it was common for Greek and Latin plays (tragedy? comedy? both? other?) to be staged for the public, though that's as far as it goes for that bit of evidence. Coffey and Mayer (Seneca. Phaedra. Introduction, text, and commentary, Cambridge 1990), though they allow that Senecan tragedy in its day could have been performed onstage, assert that it more likely will have been read for personal enjoyment or recited without staging, possibly at private gatherings — the term for that is, by the way, closet drama:

Though Seneca's primary intention was to provide a vehicle for animated recitation or declamation in which the audience was persuaded to share the illusion of an enacted drama, the possibility that his plays were performed in whole or part should not be excluded. A recent well-documented study suggests that scenes from Seneca's tragedies would make impressive, emotionally charged excerpts for the stage. (p. 15)

The study referred to in the preceding, by A. Dihle, dates from 1983. But for really ground-breaking work addressing the performability of Senecan drama, you should turn to C.J. Herington's 1966 article, "Senecan Tragedy" (Arion 5, 1966, pp. 422-471). On the question of performance, Herington writes:

Where the Senecan tragedies are concerned, . . . our only resource is the texts themselves. In these I find nothing unactable, if allowance is made for a few stage conventions that would be moderate by Jacobean, let alone Aeschylean or Restoration, standards. But that decision is, admittedly, subjective; far less subjective, if subjective at all, is the question of the speakability of Senecan drama. Practical experiment in the tape recording of scenes from the Phaedra convinced me, and I believe would convince anyone else who tried it, that Senecan dramatic verse is designed, no less than the verse of Marlowe or Racine, for its effect on the ear, not on the eye; and that that effect is shattering. Retranslated, even by amateurs, into the sound-medium, the long speeches almost of themselves generated passion, the verbal epigrams (dull on paper [Herington means the sententiae]) acquired a cutting edge, the texture and forward movement of the scenes were restored. That the verse was intended for speaking, then, I have no doubt; and if that can be admitted, the conclusion inevitably follows that it was intended for speaking by different voices for the different parts. (p. 444)

Whether or not the plays were originally meant for public performance (though Herington considers them eminently performable in the Latin original), they were, in his view, meant to be heard, with the parts spoken by individuals taking on different roles.

On the question of performability, the jury may no longer be out. In 2013, the Barnard/Columbia Ancient Drama Group staged Seneca's Thyestes in Latin, arguably, successfully.

Seneca: Life

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (ca. 10 BCE-65 CE) came from a wealthy Italian family (of not the very highest, but next-to-highest, rank, namely, "equestrian") that had settled in Roman Spain. His father was a land owner with strong interests in rhetoric and history. Relatives also achieving distinction included:

- L. Junius Gallio Annaeanus, Seneca's eldest brother, who served as governor of Greece and heard there a case against the Christian Saint Paul. This brother is actually mentioned in the Bible (Acts 18.12ff.)

- Lucan, a distinguished poet forced, like his philosopher-tragedian uncle, to commit suicide by the emperor Nero

Seneca himself, as would have been normal for any politically ambitious aristocrat, was educated in philosophy and rhetoric, in Seneca's casse, at Rome. (Athens was another venue frequented by young Romans seeking an education.) Through family connections, Seneca reached the questorship during the reign of the emperor Tiberius (14-37 CE). Soon into the reign of the emperor Claudius (41-54), Seneca fell victim to a palace intrigue. He was, as a result, relegated to the island of Corsica for seven-and-a-half years. In 49, Seneca was restored to Claudius' favor, when the emperor's new wife had him appointed to tutor her son, the future emperor Nero (r. 54-68). It was probably during these years following relegation that Seneca composed his tragedies.

For a time, Seneca, together with Nero's mother Agrippina and others, was able to keep the emperor Nero's wayward tendencies in check. However, Seneca clearly played a less than honorable role in Nero's ultimately successful plot (it took a lot of attempts) to murder his mother (59). But Seneca, the philosopher preaching moderation and virtue, also used his connections to enrich himself hugely, becoming, as he did, one of the greatest landowners in the empire. Though we should not summarily dismiss Seneca's ethical and other writings on account of his actions and record, it is hard for those facts not to color one's interpretations of the man's thought and writings.

Anyway, Seneca's influence over Nero began to wane to the point that Seneca thought it best to go into retirement; note that Seneca sought but failed to get Nero to accept his considerable wealth. Finally, after the failure of someone else's conspiracy to kill Nero, Seneca (probably innocent) and his nephew Lucan (definitely guilty) were implicated in the conspiracy and forced to commit suicide. Seneca did so in high fashion. Inviting his friends and family to witness the event, he opened his veins and discoursed on learned topics as the life bled out of him.

Is there a relationship between the writer's life and the writings themselves? Let me quote C. J. Herington on that very topic as it applies to the extremely complicated and baffling case of Seneca:

What does seem relevant is the clear fact that Seneca himself lived through and witnessed, in his own person or in the persons of those near him, almost every evil and horror that is the theme of his writings, prose or verse. Exile, murder, incest, the threat of poverty and a hideous death and all the savagery of fortune were of the very texture of his career. (In Arion 5 [1966] p. 430)

However remote, bizarre, grotesque, or unnatural we may nowadays find Senecan tragedy, it was certainly "relatable," if to no one else, then at least to Seneca himself.

Seneca: Works

Seneca wrote widely: philosophical and scientific works, the "moral epistles" (letters of an ethical-philosophical character), tragedy, an outrageous send-up of the despised — but safely dead — Claudius.

Seneca's tragedies were probably all written in the years following his return to Rome under Claudius, thus 49 CE into the reign of Nero. Still extant are:

- Agamemnon

- Raging Hercules

- Trojan Women

- Medea

- Phaedra

- Oedipus

- Phoenician Women

- Thyestes

- [The Octavia, included in your collection and assigned for our class, probably dates from the early 100s, through transmitted with tragedies authentically by Seneca]

They are quite saturated with rhetoric and replete with philosophical musings; they can also be quite gruesome in terms of their action and its description. Yet despite all that, they show considerable connection with Greek — especially Euripidean — originals, for instance, in the use of a back-story prologue and of a chorus punctuating the action with reflective passages, in debates evincing political and/or intellectual concerns, and in exploration of human psychology and motivation.

Yet the gods appear almost completely absent from these mythological dramas. Thus their focus on the human element, on the corruptive influences of power and of passions like lust and anger, point to abstracted though still relevant meditation on the dilemmas of Seneca's world. Characters caught between fate, passion, and their own, better judgment, still seem tragic, though in ways different from their Greek precursors.

Senecan Schema

To explain the relationship of plot to theme in Senecan tragedy, C.J. Herington lays out what he terms its "scheme," what I'll call the "Senecan schema" or "formula":

The scheme of a Senecan tragedy is easily defined. Although the tragedy is formally divided into five acts by the choral songs, the course of the plot, viewed as a whole, falls into three movements only, of gradually increasing length. For short, I will give them titles: The Cloud of Evil (this coincides with a formal division, the Prologue); The Defeat of Reason by Passion; finally, The Explosion of Evil, consequence of that defeat. (Herington "Senecan Tragedy" p. 449)

In other words, Herington identifies a structural-thematic principal operative in Senecan and Pseudo-Senecan tragedy generally and Seneca's Phaedra specifically. That structure consists of three "movements" as follows:

- THE CLOUD OF EVIL, which coincides with a given play's prologue, in which an atmosphere of horror and dread is carefully cultivated.

- THE DEFEAT OF REASON BY PASSION, often concentrated in the second act, where in several plays a noble and a lesser character debate — though really, REASON debates PASSION, with victory disastrously won by the latter.

- THE EXPLOSION OF EVIL. Self-explanatory, it is, of course, action inevitably resulting from passion's victory over reason. Here, "the shockwave of evil races outwards, prostrating both the wicked and the noble" (Herington 456).

By way of example, the following charts how that scheme plays out in Seneca's Phaedra:

Thematic Structure |

Dramatic Structure |

CLOUD OF EVIL |

ACT 1. Hippolytus’ chaste joy, Phaedra’s love agony. |

DEFEAT OF REASON BY PASSION |

ACT 1 cont. Phaedra’s and nurse’s debate. |

EXPLOSION OF EVIL |

ACT 2. Attempted seduction, shocked rejection. Criminal plot – “crime must cover crime” (Nurse, p. 127) |

ACT 3. Phaedra executes plan. |

|

ACT 4. Messenger speech, Hippolytus’ death. |

|

ACT 5. Phaedra’s suicide, Theseus’ grief. |

Worthy of notice is the link between Herington's schema and Stoic ethics. Thus the "tragedy" of Seneca's Phaedra lies in the failure of its key players to resist succumbing to the impulses of passion, impulses blinding them to right reason:

- Phaedra succumbs first to misguided sexual desire, then to anger when denied the object of her desire, finally, to regret causing her to commit suicide

- Hippolytus succumbs to anger towards women. Even granting the overall misogynistic tenor of Roman patriarchy of Seneca's time, Hipppolytus' passionate hatred of women seems really over the top

- Theseus, Hippolytus' father and Phaedra's husband, also succumbs to anger, in his case, rage prompting him to rash vengeance that he will soon regret

This pessimistic, moralistic take on (pseudo-)Senecan drama — tragic action as the failure of reason — arguably explains a lot. But it also seems to leave unaddressed the playwright's seeming willingness to appeal to the voyeuristic impulses of his audience, to a decidedly un-Stoic fascination with violence, suffering, and the grotesque. Perhaps, though, those two aspects, the moralistic and the voyeuristic, are merely two sides of the same coin.

Seneca's Phaedra

Dating from perhaps earlier on in the chronology of Seneca's tragedies, the Phaedra combines two story-telling motifs:

- That of the evil stepmother. (Hippolytus will die as a result of his stepmother's falsely accusing him of attempted rape), and

- That of Potiphar's Wife, a motif named after the Biblical story of how Joseph was falsely accused by married woman he had been propositioned by and had turned down

In the story, Theseus, son of the sea god Neptune and foster son of the Athenian king Aegeus, has a son of own: Hippolytus. His mother was the now-dead queen of the Amazons, a race of man-hating women warriors from far to the east. Hippolytus, addicted to hunting and to the outdoors, has sworn himself to eternal virginity. In the meantime, two things:

- Theseus has married a woman from Crete, one Phaedra, who will fall in love with Hippolytus. Phaedra is the daughter of Pasiphae, notorious for her love affair with a bull, and is the sister of Ariadne, with whom Theseus had earlier eloped, and whom Theseus then abandoned on an island. She is also half sister of the half-man, half-bull Minotaur, the result of her mother's taurophilic tendencies.

- Hippolytus is son of Theseus by a previous wife, the Amazon Antiope (the Amazons were warrior women from the eastern Mediterranean). Theseus slew Antiope for reasons that, in this play, are somewhat obscure.

- Theseus has set off with his friend Pirithous for the Underworld, there to kidnap Proserpina, queen of the dead.

In Theseus' absence, Phaedra has fallen in love with the handsome but standoffish Hippolytus. The complications that creates, and how characters in the play will deal with same, will be for you to find out, though suffice it to say that will involve Theseus wishing the last of the three wishes his god father had promised him. . . .

Important in this play is its rhetoric. Above, you'll have read about the importance of rhetoric at Rome during the time of this play's composition; in Seneca's text you'll want to be on the lookout for that. Among other things, keep look for pithy phrases and sentences loaded with often heavily ironic, and at times, riddle-like, meaning, what the Romans called sententiae. Noteworthy is the following:

A man who can do much would like to do

More than he can. (Nurse, p. 106)

That sententia is rather tamely translated in the Penguin edition. The Latin reads, "quod non potest vult posse qui nimium potest" (line 215), better rendered, "A man with excessive power desires a power that is unattainable" (trans. Coffey and Mayer). As such, the sentiment expresses something close to the Greek-tragic "law of hubris and ate." Yet, in compressing within itself multiple levels of irony (e.g., excessive power means a kind of stunning impotence — note the triple repetition of forms of posse, "to be able," "to be empowered"), it somehow moves into the realm of the (characteristically Roman) over-the-top.

Can you find more such quotes in your text?

Connected with that is, arguably, a fascination with the spectacular, the monstrous, the grotesque, the bizarre. That has been connected by scholars with the Roman interest in outsized, violent shows like chariot racing and gladiatorial combat. See if you can find evocations of that, too, in your text.

Themes, Issues, Further Questions

Genre

Basically, what is "tragic" about this tragedy? Now, we don't have to be essentialist about that. Still, how does this tragedy fit into the tradition examined so far: classical Athenian, Republican Roman? How does this play, understood as tragedy because somehow part of that tradition of tragic plays, nevertheless force us to rethink our definition of tragedy, especially given its over rhetoricism? What is tragedy anyway?

Character, Theme, Gender

Phaedra is a character who alleges a sexual violation and then, in full view of her husband, kills herself. How, then, is she like, how unlike, the Roman suicide Lucretia in Accius' Brutus? More generally, can we begin to detect specifically Roman and/or political themes in this Roman play treating Greek mythology, evoking philosophy, and ending with a grisly death off stage and a suicide on stage?

And what do you make of Theseus' final speech (pp. 149-150), in which he dwells at length on the death and soon-to-happen funeral of his wrongly accused son, and then devotes two lines to the less honorable burial of his wife? Does Phaedra deserve that? Is that simply a plausible reaction from Theseus, or what do you think?

The previous was a gender question. Also on the subject of gender, what do you make of Hippolytus' impalement through his groin on a sharpened tree stump — symbolic somehow? and what about Hippolytus himself: wholly innocent or culpable on any grounds?

Notes

Here follow notes keyed into the pages of your text. They should help with some of the more obscure references.

99 Note how this prologue, spoken by Hippolytus, doesn't really supply backstory, as in a tragedy by Euripides.

99 Land of Cecrops. Athens and its environs. In the lines that follow ("In the shadow of Parnes’ height," etc. etc.), Hippolytus simply evokes the countryside surrounding Athens. In movies they call that the "establishing shot." "Establishing shots" are big in ancient, and especially Roman, literature. Note also all the evocation of hunting.

100 Molossians, Spartans, etc. These are breeds of hunting dogs. The blood-lust of some of those dogs foreshadows the play's ending. Hippolytus will become the hunted.

100 "Huntress divine." Diana, the Roman virgin goddess of the hunt. (Cf. Greek Artemis.) Hippolytus has sworn to remain a virgin.

103 "Is this the evil spell / That bound my mother, my unhappy mother?" Phaedra's mother was Pasiphae, who fell in love with a bull and gave birth to the Minotaur, half human, half bull. Phaedra, in other words, fears that a family curse — that of illicit love — has forced her to love her stepson, Hippolytus.

103 "This comes from Venus" — Venus = Aphrodite, gosddess of love. Venus hates the Sun and his descendants, Phaedra included; the Sun revealed Venus' love affairt with the god Mars.

100 auroch. A kind of European bison.

101 top. Those are far-away places. This is how far Diana's power reaches.

101 wain. Wagon.

102 Phaedra's speech serves as a kind of delayed prologue supplying backstory. Her burning heart is her lust for her stepson, Hippolytus.

102 "comrade in arms / To an audacious suitor Seneca" — Theseus and his friend Pirithous are off to the underworld to kidnap Proserpina, queen of the dead. Phaedra is jealous.

103 Is this the evil spell That bound my mother" — Phaedra's mother, Pasiphae (a daughter of the sun), fell in love with a bull; Phaedra, with her stepson.

103 Venus. Goddess of love, = Greek Aphrodite.

103 Jove, aka Jupiter. Roman king of the gods, = Greek Zeus.

104 "In Lethe’s depths, walking the shores of Styx" — in the Underworld, land of the dead.

104 "– what of him who rules The hundred cities and the wide sea roads, Your father?" — Minos, king of Crete.

105 "The invincible winged god." Love, or Cupid, son of Venus. = Greek Eros.

106 Phoebus. I.e., Apollo.

107 "A true Amazonian." The Amazons were mythical women from the Russian/Central Asian steppe. They were dedicated to hunting and war. (We know of no actual Amazons from antiquity, though their myth might have had a basis in certain aspects — the position of women, etc. — of Scythian society.) Their society was matriarchal; to Greeks, they expressed threat to the patriarchal status quo. Theseus had to defeat an invading army of Amazons. Antiope, their leader, was mother of Theseus' son, Hippolytus. Hippolytus, averse to relations with the opposite sex (to sex altogether), and dedicated to hunting and the great outdoors, can thus be spoken of as, in a sense, "a true Amazonian."

108 "I'll join my husband. By death I shall avert transgression." Phaedra will "join" her husband because, once she's committed suicide, she be in the land of the dead. That's where Theseus is, on an adventure and very much alive.

108 "from the high rock of Pallas?" — i.e., from the Athenian acropolis.

108 Ariadne. Ariadne is Phaedra's sister. Theseus, after killing the Minotaur, fled Crete with Ariadne, his lover and accomplice. So she represents another example, along with Pasiphae, of illicit love connected to Phaedra.

109 CHORUS. Note how this chorus makes no pretense to any dramatic identity in the play; they're not "elders of the city" or "attendants of the queen" or anything like that. In their extended odes (as here), they're there to comment on action and themes and to divide the play into acts. Elsewhere, the chorus/chorus leader interacts with characters, as in Greek tragedy.

109 "daughter of the never gentle sea." Venus.

110 "Phoebus came down to Thessaly" — Phoebus = Apollo. This is a reference to the myth of Alcestis and Admetus.

110 neatherd. A herder of cattle.

114 a woman of Maeotis / Or Tanäis" — Maeotis = the Sea of Azov, bordered by Crimea and Russia. Tanäis = the river Don. The Amazons, barbarian warrior women, were believed to come from the Russian-Ucranian steppe north of the Black Sea. Phaedra wants to be an Amazonian huntress and to join half-Amazonian Hippolytus' hunt. Pontus = the southern shore of the Black Sea or the Black Sea itself.

119 "So, I think, / Men lived in the olden days" — Hippolytus spends lines and lines describing (a) the progressive corruption of human kind, their fall from innocence and grace, as a development parallel to, and caused by, (b) their ever increasing technological savvy and, with that, their growing ambition. It might seem out of place but it's, I think, very much in character. This is mansplaining (and passive-agressive misogyny) on a grand scale.

120 "Stepmothers" — Hippolytus' misogyny and hatred of stepmothers certainly shocks. But maybe it's meant to. This is over-the-top anger and animus; Seneca the Stoic would disapprove. Hippolytus is no hero, but he's also hopelessly naive and tactless. If his aim is, perhaps, to tell the Nurse to get lost, he could have done so a lot more tactfully.

124 "The Cnossian monster." The Minotaur, on Crete. Theseus killed the Minotaur.

124 "And in his face there was the face of Phoebe, Your ancestor – or Phoebus, mine" — this is poorly translated and confusing. "Phoebe" (= feminine "bright") refers to Hippolytus' patron deity, Diana. "Phoebus" (= masculine "bright") is Phaedra's ancestor, the Sun. As commentator's note, Phaedra plays with the idea of Hippolytus as possessing a kind of gender-ambiguous beauty.

124 "Scythian roughness" — Hippolytus' Amazonian ancestry.

126 "Father, I envy you; you had a stepmother, / The Colchian woman, but my enemy / Is one far worse, far deadlier than she." Hippolytus' enemy is Phaedra. Theseus' stepmother is Medea, because Medea, after fleeing from Corinth, sought refuge with Aegeus, Theseus' father.

127 "Help us, all Athens!" The Nurse is trying to protect Phaedra from condemnation by making Hippolytus out to be a would-be rapist and Phaedra, an innocent victim.

127 Corus. Corus or Caurus was the northwest wind.

128. "O beauty, but a dubious boon Art thou to man, brief gift of little stay, Lent for a while and all too soon Passing away." Beauty (Hippolytus') as a "dubious gift" seems to reflect Stoic teaching, according to which beauty, health, wealth, etc. don't matter. All that matters are virtue and wisdom, which for Stoics are basically the same thing.

128 Phoebe. As before, the Moon.

128. Hesperus. The evening star, that is, the planet Venus.

129. Naiads, Dryads, Pan. The first two are woodland nymphs. The third is a god of the wilds.

130. "That neck is not less lovely than Apollo’s." Hippolytus' neck. Apollo was the paragon of youthful male beauty.

130 Parthian. The Parthians were an Iranian people renowned for their skill at archery.

131 "His face Is like the face of young Peirithous." Peirithous was Theseus' friend, and accompanied T. to the Underworld to kidnap Proserpina (proh-SUR-pih-nə), queen of the dead.

131 Cerberus. The three-headed dog that guarded to entrance to the underworld. To bring Cerberus to the upper world was one of the labors assigned to Hercules (Latin = Greek Heracles).

132. Phlegethon. The underworld river of fire.

132. "THESEUS: Unbar the doors Of the royal house." For a Roman audience, this whole Phaedra suicide (split between acts 3 and 5) will have recalled the suicide of Lucretia, a theme treated in Accius' Brutus.

135 Worlds that lie upside-down beneath our feet." Seneca, with his interests in philosophy and science, knew perfectly well that the earth is a sphere.

136 Dis. Another name for Pluto, god of death and the underworld.

138-139 southern Auster ... Ionian waters ... the head of Leucas. Respectively, the south wind; the Ionian sea, between western Greece and Italy; Leucas = Lefkada, an island off the western coast of Greece.

139 "Was this the birth Of one more Cyclad?" The birth of another island in the Cyclades chain, in the Aegean sea. More references to Greek geography follow.

139 "As when the huge spouting leviathan’s / Wide mouth...." "Leviathan" here translates what in the original means "whale." The breathing of the sea-bull monster is compared to that of a whale.

141 Phaethon. Phaethon, the son of the Sun, wanted to have a chance to drive his father's chariot on its daily trip across the sky. Bad idea: Phaethon makes a mess of it. Chariot nearly totaled, Phaethon completely totaled.

143 Boreas. The north wind. (Or just the north.)

143 "Phrygian forests of the Mother Goddess." The cult of Cybele, here, the "Mother Goddess" (aka the Great Mother of the Gods) was important not just to Phrygia but to much of Asia Minor (= Anatolia = Turkey). Her cult was established in Rome in 204/3 BCE.

144 "Pallas, whom all the Attic race adore" Athena, worshipped by all Athenians.

145 Tethys. = wife of Oceanus, god of the ocean.

145 Sinis, Procrustes, Cretan Bull (i.e., Minotaur). These are monsters previously killed by Theseus in the course of his heroic exploits.

146 Stygian stream. Tartarean lake. burning river. Underworld bodies of water. I.e., the Underworld.

147 "Taenarus, and Lethe’s river." Taenarus, entrance to the Underworld. Lethe, the river of forgetting, in the Underworld.

148 "The father of my friend Peirithous shall rest." Ixion, punished by being bound to an eternally spinning fiery wheel.

149 "I had to ask my father for his aid." Theseus' father is often given as Poseidon-Neptune, god of the sea. Neptune granted Theseus three prayers, the third of which he unleashes on Hippolytus. But Aegeus, king of Athens, is also given as his father. In this play, both seem to be Theseus' dad — go figure.

149 "THESEUS: Yes, bring your burden, bring me those remains." The image of the dismembered Hippolytus cannot but evoke associations with Pentheus in Euripides' Bacchae. Theseus' effort to "re-member" Hippolytus (put him back together, pun intended) are ultimately futile; they'll all be consigned to the funeral pyre. Theseus' anger, and resulting poor judgement, have annihilated his world.