Reading Assignment, Text Access

Read:

This Study Guide, all of it, with SWA prompt, helpful notes, etc. Study guides are always a required — and useful — read.

Lucian. The Dream, or, Lucian's Career, pp. 215-233. In: Harmon, A. M. Lucian. Volume III. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1921.

_____. Slander, on not Being Quick to Put Faith in It, pp. 261-293. In: Harmon, A. M. Lucian. Volume I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921.

SWA Prompt

Let's treat this as a critical-thinking exercise. The prompt may seem to focus on details, but those details are meant to serve as lenses offering broader insight into the assigned readings. So, . . .

What role does envy play in these two texts? Why does Lucian's narrator in Dream allege that the beating he gets from his uncle stems from envy, phthonos? Is that the same as the envy implied by the translator's use of "envious" to translate zēlōtos? (See notes, below.) What about envy in Lucian's Slander: does it play a role similar to, or different from, the one it plays in Dream?

Introduction to Texts

Sophia, agōn, paideia, pathos; "skill, contest, education, emotion": those themes lie at the center of today's readings and of this semester's course. Lucian's Vision concerns education and the attractions of a career in rhetoric. Slander addresses the dangers one courts when pursuing one's ambitions in rivalry with others. We won't have had time to fill in all sorts of important background; for now, try to feel as if you're touring some very old place but very new to you. What is the overall layout? What stands out? What would you want to take a "picture" of to share with others? What will you tell others when you get home?

Concepts

A few words on key concepts mentioned above are in order (though note that these concepts are also explored on the "Terms" page). . . .

sophia is usually translated as "wisdom," but in ancient Greek it could, and often did, mean "skill," "craft," or "cleverness," a way with words, for instance, aka, eloquence. Those possessing sophia in the sense just mentioned could be termed "sophists" (sophistai, singular sophistēs), especially if they professed to teach sophia to others, and most especially if they took money for it. Under the Empire, in the Greek-speaking East, "sophist" referred (usually in a commendatory sense) to elite practitioners and teachers of rhetoric.

agōn means "contest," whether a formal contest with prizes, a legal trial — anything involving rivalry or the effort to excel. Much of this course is about the culture of competition ("agonism") in the Roman Imperial East, ca. 1st through 3rd cent. CE.

paideia means, literally, "education." For our period, it refers as well to the cultural capital that comes from a deep knowledge of Greek language, literature, and culture, and in particular, rhetoric. But it also had to do with personal comportment, speech, dress, social savoire faire — breeding, in other words. For the educated elite, paideia was, if not everything, then pretty close.

pathos means "emotion" or "passion." In our readings, what emotions or passions have to do with agōn-"competition"?

Author Notes

Lucian (ca. 120-ca. 190 CE), Greek Loukianós (from Latin "Luciánus"), was born in the town of Samosata, present-day Samsat, in what is now Turkey; in his time it formed part of the Roman province of Syria. Lucian was not himself Greek, but he had a thoroughly Greek education and pursued the career of a sophist, a teacher-performer of rhetoric. On the topic of Lucian's ethnic identity, in the Double Accusation, the author makes a fuss over his foreignness, and how his education and eloquence opened doors for him throughout the Empire. Says "the Syrian" (i.e., Lucian), "[Rhetoric] made a Greek of me!" (Double Accusation sect. 30, trans. Fowler).

As a sophist, Lucian seems not to have entered the front ranks of the profession (he wasn't a superstar like Polemon or Herodes Atticus), but he did get a chance to bring his writings to the attention of the emperor Lucius Verus. The fact that we have so much of what he wrote attests to his popularity after his death. Lucian traveled widely, spending time in Italy, Gaul (present-day France), and Greece. In the end, rhetoric did not pay the bills, and he took the position of bureaucrat in Roman Egypt.

We have all manner of prose from Lucian, including declamations, dialogues, and assorted essays. He was a master of humor and irony; today, we consider him a satirist.

The Dream, or, Lucian's Career

The Greek in the manuscripts calls this work Peri tou enupniou ētoi bios Loukianou, "On the Dream, or the Life of Lucian." This is our paideia piece, a reflection on education in "the classics," and the cultural and professional cachet that such an education was supposed to bring.

Whatever its autobiographical accuracy, Lucian's Dream provides an amusing look at how rhetoric could be viewed as a high-prestige field of endeavor. The narrator does not, to be sure, anywhere insist on his identity with the author, but even if he did, he and his narration are still dramatic creations. Be that as it may, Lucian's Dream presents itself as a speech delivered before an audience; we can tell that because the narrator humorously refers to hecklers in the audience (pp. 231-233). It seems, moreover, to exemplify the kind of prolalia, or "warm-up piece," that sophists used an an opener when performing live before an audience. Indeed, Lucian's Dream could be read as an advertisement, possibly an ironic advertisement (?), for the kind of rhetorical instruction in which sophists like our author specialized.

The dream that the narrator narrates is one that persuaded the narrator to pursue paideia instead of an apprenticeship in a less prestigious trade. As such, the piece echoes and alludes to all sorts of stuff in the ancient Greek literary tradition:

- Ancient Greco-Roman literature is full of dreams as moments of clarity and revelation for the dreamer

- The ride on the flying chariot perhaps is meant to recall the myth of the chariot of the soul in Plato's Phaedrus. It explicitly recalls Triptolemus' mythological ride on a horse-drawn flying chariot. Triptolemus, like a kind of culture-hero Santa Claus, in the course of his flight spread culture among the people's of the earth

- Lucian introduces Sculpture and Education as quasi-divine women. That recalls the (older) sophist Prodicus' (400s BCE) story of the choice of Heracles. A young Heracles, having found himself at a crossroads in life, had to choose between Virtue and Vice, likewise personified as women

- This narrator's choice also recalls the mythic Judgment of Paris, who had to choose which of three goddesses, Hera, Athena, or Aphrodite, was the most beautiful

- There are also echoes of Hesiod's (ca. 700 BCE) encounter with the Muses, how they chose him to be a poet

- As a student of mine once pointed out, there is as well an evocation of Achilles' choice between a brief but heroic life and a long but obscure life in Homer's Iliad (8th cent. BCE)

- There is a key comic evocation in the tug-of-war between Sculpture and Culture, each pulling on Lucian, each wanting to claim him for themselves. In Aristophanes' Assemblywomen (ca. 393 BCE), two elderly ladies intent on having their way with a young man similarly start to pull him this way and that.

- There is arguably yet another evocation: the choice between traditional and sophistic education in Aristophanes Clouds (423 BCE)

In recalling the literary-rhetorical tradition, Lucian's essay is both true to its theme of paideia and typical of literature of the second sophistic.

Dream: Notes keyed into page numbers

217. Note that the narrator, whose origins are in the tradesman class, has already had a basic education: he can read and write. The wax from which he forms figures comes from the tablets on which people wrote letters, took notes, etc. It was easily erased and reused.

219. The narrator alleges that his uncle beat him out of "jealousy" (envy), phthonos. Why would he think that?

219. "Two women, taking me by the hands, were each trying to drag me toward herself with might and main; in fact, they nearly pulled me to pieces in their rivalry." See above on literary allusions and echoes.

223. Sculpture's name in Greek is Hermogluphikē, literally, "the art of herm carving." Education's name in Greek is Paideia. "Envied" here and elsewhere in the piece, when it refers to admiration (rather than malice), is zēlōtos, from zēlos, usually translated as "emulation."

223. Education says that the narrator, should he achieve greatness as a sculptor, will always be a "mechanic," a term that, in 1902, could, evidently, refer to anyone who worked with their hands. The Greek word is banausos, meaning a member of the non-elite working class.

225-227. Education offers the narrator a path to social advancement.

229. See above for Triptolemus.

229. "princely purple" — Purple dye was extremely expensive to produce. It was closely associated with persons of high rank.

231. "Even as I was speaking, 'Heracles!' someone said, 'what a long and tiresome dream!' " The piece presents itself as being narrated before an audience, including hecklers.

Slander, on not Being Quick to Put Faith in It

Lucian presents this piece, which he calls a logos, a "speech" or "lecture," almost as a public service announcement. Just as television used to be full of messages warning people not to smoke, this essay warns readers to be on guard against slander or "trash talk," in Greek, diabolē.

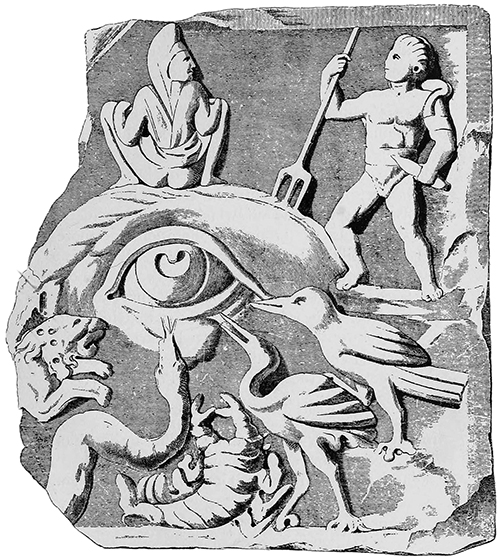

Note that the work contains a description of a lost narrative painting, a depiction of slander in action, by the Greek artist Apelles (later 4th century BCE). . . .

The image just below dates to much later than Lucian's essay; it is Sandro Botticelli's attempt, ca. 1494-95, to recreate Apelles' lost, and possibly fictitious, original:

Lucian claims that the painting was inspired by the painter's close brush with death after being slandered by a rival at the court of the king of Egypt. Although the background story that Lucian tells must be largely a fiction, the general contours of the situation it describes is of great interest. That situation is as follows: The painter Apelles, while in residence at the court of the Egyptian king, had a rival in one Antiphilus. To get a leg up on Apelles, Antiphilus tried to frame him for treason. Apelles would have lost his head, had another of the king's courtiers not vouched for him.

At the level of fact, this couldn't have happened. Apelles was active in the later 300s BCE; the events described in the essay date to 219 BCE. So far as I can tell, Lucian is the only ancient author to mention either the incident or the painting it supposedly inspired. This pattern, though — rivalry, envy, slander, credulous ruler, danger —, figures prominently in ancient Greek sources, especially from the Imperial period.

The figures described in Lucian's essay (pp. 365-7) correspond to those depicted in Botticelli's painting. They are mostly (not entirely) allegories, that is, personifications of emotions, abstractions, and so on. The king is the seated figure at the far right; he has long, you might say, easily fooled, ears. The naked youth is the victim of slander. That dodgy, hooded guy holding up his hand to impede the king's vision is Envy. The girl with the torch, and dragging the young man, is Slander herself.

Apart from the painting and the scenario it depicts, at least three things in the essay are of interest to us. First, there is the description of various competitive situations, including athletics, familiar to Lucian's audience. Then there are the emotions, notably including envy, phthonos, that arise from (among other things) competitive situations, and that prime people to utter, and to listen to, slander. Finally, there is the prominent role played here by "kings," basileis (singular basileus). Their paranoia in the face of perceived threats, their failure to do due diligence, and in particular, their frailty in the face of flattery become, whether separately or in combination, the enabling factor allowing slander to wreak havoc on its victims. Given the fact that, for Lucian's Greek-speaking audience, the go-to word for the Roman emperor will have been basileus, "king," it seems not unreasonable to suppose that Lucian somewhat obliquely addresses the challenges and hazards faced by provincial elites when having to deal with the at times capricious Roman Imperial authorities.

Slander: Notes Keyed into Page Numbers

367. "She [Slander] is conducted by a pale ugly man who has a piercing eye and looks as if he had wasted away in long illness; he may be supposed to be Envy." Envy's "piercing eye" is the evil eye; his "wasting away" reflects conventional ideas of envy as eating away at the envier from within.

369. "Solon and Draco." Solon and Draco were two great lawgivers of Athens from the archaic (= pre-classical, ca. 700-500 BCE) period.

373. The whole of section 10 is crucial not simply to the essay but to much of our course. Note the role of emotion in all this ("the courts of kings . . . , where envy — phthonos — is great"). One detail I'd like to highlight is the analogy with gladiators ("All [courtiers] eye one another sharply and keep watch like gladiators to detect some part of the body exposed"). Gladiators, in Greek, monomákhoi, in Latin, gladiatores, were hugely popular all over the Empire, but they were originally a Roman thing, not Greek. I suspect this isn't the only Roman resonance in the essay. (See above, on "kings.")

379. "... the only person who did not wear women’s clothes during the feast of Dionysus." It was normal for men seeking to be initiated into the secret rituals of Dionysus to cross dress. Dionysus was the god of crossing boundaries, including gender boundaries, and this king of Egypt (Ptolemy XII, 112-51 BCE), in styling himself "the new Dionysus," would not have taken kindly to any disrespect shown to Dionysus worship.

379-81. Alexander, yes, that Alexander, that is, "The Great" (356-323 BCE), king of Macedonia and conqueror of a vast empire. He more than anyone spread Greek language and culture from Greece proper to Libya and Egypt, Anatolia (Turkey), the Middle East, Iran, and parts of Central Asia. Hephaestion was a commander, friend, and probably lover of Alexander. To memorialize his dead friend (324 BCE), Alexander elevated him to the status of a god.

389 ff. Lucian is now answering supposed objections to his argument.

389. Aristides, Themistocles. Athenian leaders and political rivals in the early 400s BCE. Aristides was renowned for justice; Lucian alleges that his opposition to Themistocles resulted in unfair treatment of the latter, a debatable point.

389. Palamedes, a Greek hero at Troy and the "the epitome of the skilful inventor" (Brill's New Pauly). So great was Achilles' envy — phthonos — of Palamedes that he contrived to have the latter framed for treason. Palamedes is, therefore, a close parallel to Lucian's Apelles.

389-391. Socrates, the Athenian philosopher, was tried and convicted for impiety in 399 BCE.